[ad_1]

“Self-portrait” by Angelica Kauffmann, circa 1770 to 1775. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The 19th-century Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot once said, “I do not think any man would ever treat a woman as his equal, and it is all I ask because I know my worth.” Morisot, at times, expressed frustration that her painterly skills were described—in a condescending tone–as superficially light and feminine.

A fixture of the Parisian art scene, Morisot was positioned for commercial and artistic success. However, even this founding member of art’s most famous movement (and sister-in-law to Manet) faced barriers to recognition based on her gender. Female painters in 18th and 19th century Europe faced similar dilemmas—fame and fortune were possible, but their gender could pose additional barriers to formal training, recognition, and exhibition.

Despite these difficulties, female painters advanced new techniques and pioneered new styles of representing their subjects. They painted emperors, kings, and princesses. Their works were coveted by nobles across Europe and robber barons across the Atlantic. Although there has never been a time when women were not involved in artistic pursuits, their works remain underrepresented in the collections of museums. Often, their works have been mistakenly attributed to men by (typically male) viewers and scholars.

The genius of female painters is still being recognized as works are reappraised and female artists rediscovered. Read on to learn more about female painters from 18th and 19th century Europe who rivaled their male counterparts for commissions and prestige.

Learn about female painters from 18th and 19th century Europe who have been pioneers in their fields.

Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807)

“Portrait of Ferdinand IV of Naples, and his Family” by Angelica Kauffmann, 1783. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Born in Switzerland, Angelica Kauffman was the daughter of the muralist Johann Joseph Kauffman. She received artistic training while acting as her father’s assistant from a very young age and copying the works of Old Masters as they traveled for commissions. As a young woman, she also trained in Italy where her historical paintings and portraits were well received.

After moving to London in 1766, Kauffman was one of only two female founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts. Aside from her popular portraits of aristocratic sitters, the artist depicted many classical and allegorical scenes. She was a prominent figure among her contemporary Neoclassical painters in the late 18th century.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842)

“Marie Antoinette and her Children,” by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, 1787. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun was a Parisian painter and is still one of the best-known female artists of her era, with work that straddled the transition from Rococo to Neoclassical tastes. Today, her portraits of the doomed French Queen Marie Antoinette are well known. At the time, the portraits raised Le Brun’s profile among the courtiers of the Ancien Régime. Nobles from Russia, Austria, and Italy also solicited her works after she fled France in 1789 at the onset of the revolution.

Like other Neoclassical painters, she at times depicted her subjects as characters from mythology. Years after the revolution, the favorite painter of the late queen was eventually able to return to Paris, where her work was often exhibited in the prestigious Salon.

Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757)

“Young Woman with a Parrot,” by Rosalba Carriera, circa 1730. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Rosalba Carriera was born in Venice. Unlike many female artists, she did not learn to paint from a male family member. While it is unknown where she learned, she became so skilled that she eventually wrote a manual of techniques. Her early works of miniature paintings were quite popular with the European aristocrats who traveled through Venice in search of art and luxury. They were so popular that forgeries began appearing.

She then made her mark in the realm of portraiture by using pastels to create dreamy Rococo images. Pastels were not a popular medium for formal portraiture until Carriera popularized them. Over her many years active, she marketed her art well and painted countless royals and nobles—dying a wealthy woman in 1757.

Marguerite Gérard (1761-1837)

“Le Chat Angora,” by Marguerite Gérard and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1780s. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

In 1775, the teenage Marguerite Gérard traveled to Paris from her home in Grasse. She lived with her sister Marie-Anne Gérard and her brother-in-law Jean-Honoré Fragonard in the Louvre—a former royal palace that then served to house artists and their studios. The elder Gérard sister painted miniatures while her husband was a well-respected Rococo painter. The younger Gérard learned from Fragonard.

First, she seems to have practiced by copying his paintings in her own etchings. As a painter, she focused on genre art depicting scenes from everyday life. Her work was popular with aristocratic patrons. Her 1806 work The Clemency of Napoleon was purchased by the emperor himself. Many of her paintings were also sold as affordable engravings, making her an artistic household name during her lifetime.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1803)

“Self-portrait With Two Pupils,” by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1785. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

A young Parisian woman, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard began painting miniatures before transitioning to full-scale portraits in pastels and oil. Like her contemporary Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Labille-Guiard was a popular choice among French royals and nobles in search of portraits. She was one of only four women who were allowed into the French Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Her bold, fashionable depictions of elite women were greatly admired.

Unlike Vigée Le Brun, Labille-Guiard did not have to leave Paris after the revolution, however, she did lose much of her noble clientele. Labille-Guiard is often remembered for her subtle statements on the place of women as students of the arts. Her portrait with two pupils—exhibited at the salon in 1785—is seen as a statement of quiet contradiction to the standing rule that only four women could be academy members at once.

Marie-Denise Villers (1774-1821)

“Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes,” by Marie-Denise Villers, 1801. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Parisian painter Marie-Denise Villers was a member of the artistic generation coming to age in France after the revolution. One of three female artists in her family, she studied painting with François Gérard and Jacques-Louis David—as well as the female painter Anne Louis Girodet Trioson. The above Neoclassical work depicts the young Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes. It was long thought to be a painting by David. However, in the 20th century, experts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art rejected this attribution and hypothesized instead that the painting is by Villers.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

“The Highland Shepherd,” by Rosa Bonheur, 1859. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The 19th-century Realist painter Rosa Bonheur was known for her stunning paintings of animals ranging from horses to bulls to rabbits. Living in a French country chateau she purchased, Bonheur never married. She wore her hair short, obtained a then-necessary permit to wear men’s clothes, and even owned a pet lioness. She was the first female artist awarded the Légion d’Honneur after Empress Eugénie visited her studio. The empress famously declared that “Genius has no sex” after viewing Bonheur’s paintings.

Bonheur became very famous during her lifetime. She met countless heads of state and was appreciated by the artistic likes of Eugène Delacroix and John Ruskin. She found success in the Paris Salon and was received as a celebrity of the art world in London. Her most famous work, The Horse Fair, was eventually purchased in 1887 by American Cornelius Vanderbilt for $53,000 (about $1.5 million in today’s currency). The enormous canvas now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Despite all her success in her lifetime, Bonheur’s legacy eventually faded into obscurity with the advent of Impressionism and her death at the end of the century. However, in 2020, a woman named Katherine Brault purchased Château de By—intending to revitalize Bonheur’s home, which had been out of use. With her daughters, Brault has lead a crusade to preserve the memory of the once-renowned female artist in a museum dedicated to her work.

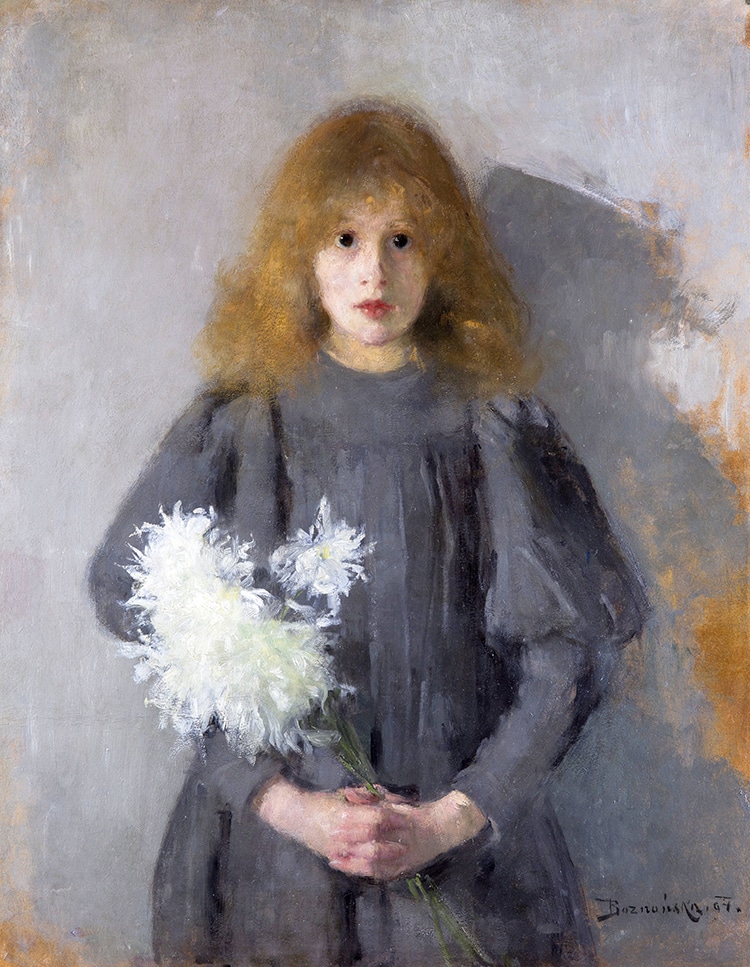

Olga Boznańsk (1865-1940)a

“Girl with Chrysanthemums,” by Olga Boznańska, 1894. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Public domain)

The Polish painter Olga Boznańsk began her professional career in Krakow in the late 1880s. She studied with artists in Germany and learned to specialize in portraits. At the turn of the century, she moved to Paris. She was awarded the Légion d’Honneur in 1912, among countless other honors.

Boznańsk primarily painted portraits of women and children, often with flowers and a sense of innocence. Although she overlapped with the tail-end of the Impressionism heyday, she did not consider herself among them. She said once about her work, “My paintings look great because they are the truth, they are fair, there is no narrow-mindness, no mannerism and no bluff.”

Berthe Morisot

“The Artist’s Sister at a Window,” by Berthe Morisot, 1869. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Berthe Morisot was an important Impressionist painter who was fully ensconced in the painterly world of the late-19th century Paris. Although she first exhibited in the esteemed Paris Salon in 1864, she joined the “rejects” (her fellow Impressionists) in the monumental exhibit of 1874 which came to define the movement. Her works were in oil, watercolor, and pastel. While her light brush strokes can be seen in the works of some male Impressionists, her skills were often derided as “feminine.” But from formal portraits to Parisian scenes, her paintings hang in the world’s finest art museums.

Socially, Morisot was of an upper-class background. She was the great-niece of Jean-Honoré Fragonard—the artist who trained Marguerite Gérard. Morisot married Eugène Manet, brother of her friend the painter Édouard Manet. Édouard Manet painted Morisot several times and would go on to paint her daughter Julie as well. Pierre-Auguste Renoir would also paint mother and daughter.

Despite the predominantly masculine world of the Impressionist painters, Morisot was respected for her talent. Referencing the 1874 exhibit with the likes of Manet and Monet, a critic said of the revolutionary painters, “five or six lunatics of which one is a woman…[whose] feminine grace is maintained amid the outpourings of a delirious mind.” Today, the works of Morisot are as coveted as many of her male contemporaries.

Related Articles:

Online Database Features Overlooked Female Artists from 15th-19th Centuries

28 Iconic Artists Who Immortalized Themselves Through Famous Self-Portraits

5 Contemporary Textile Artists to Celebrate During Women’s History Month

9 Pioneering Female Artists to Celebrate on International Women’s Day

[ad_2]

Source link